Harriet Imler was born June 1, 1843 at Deer Creek, Pickaway County, Ohio, the tenth of twelve children of her parents, George and Sarah Betz Imler. Her parents, both born in Pennsylvania, were “Pennsylvania Dutch” and spoke the German language. Exactly when the Imler family moved to Allen County is not known, but they were living in Shawnee township by the September 1850 agricultural census.

The Imler family was members of the Saint Matthews Evangelical Lutheran Church in Shawnee Township, Allen County. The first church was a log structure, and the church services were conducted in the German language. The earliest records of the church are lost, except for an 1844 list of founding members. George Imler is not on this list, indicating the family was still in Pickaway County. In 1851 a frame building was erected and George Imler appears on the donor list for that building.

Allen County was heavily wooded when the first settlers arrived and most families lived in log houses. The following was taken from a history of German Township written by S.D. Crites in 1909 and printed in the Lima (Ohio) News on May 29, 1909. The Crites and Imler families were neighbors.

“The typical cabin was built of round logs, chinked and daubed, enclosing one room fifteen by eighteen feet. There was but one door and opposite it a window. The door was of split plank, hung on wooden hinges with a wooden latch which was fastened within to a string. The string in day time protruded without through a small hole but at night was withdrawn within. Hence the old saying when inviting friends to call: ”You will find the latch string out.” On the interior the floor was of puncheons, the hearth was of rock usually of nature’s own hewing. The fireplace was wide, and deep enough to receive logs eight or even ten feet long. There was an iron crane or wooden pole in the chimney to which was attached a chain which ended in a hook. From the hook was suspended a pot which was used for various purposes. The other cooking utensils were a skillet, iron teakettle, a dutch oven and a wooden tray. A chest contained the linen and wearing apparel of the family. Over the door rested the indispensable flint lock, on a rustle rack. In the rear of the room stood a bed with a curtain around its legs to conceal the trundle bed used by the children. The loft was reached by means of a rough ladder at the rear of the room. The loft served the purpose of dormitory, larder and tool house. It was a private bedroom. It also contained the winter supplies: hominy, corn, pumpkins, seeds of all kinds, jerked venison, dried corn and fruits, hickory nuts and walnuts. The tools were a maul and wedge, crosscut saw, drawing knife, an auger, a frow and a broad ax. The roof of the cabin was covered with clap-boards held in place by ridge poles.”

On February 5, 1861 Harriet, aged 17 years and four months, and William Clark, aged 27 years and four months were married by the Justice of the Peace at Allen County, Ohio. Eight months earlier on the June 1860 federal census, widower, William Clark and his two small children were living with his former in-laws, the John Searfoss family. William, who was illiterate, had no real nor personal property. Why would a 17 year-old girl marry a penniless, illiterate, widower, ten years her senior and with two small children? Was it love or a means to get out of her parent’s home? I doubt we will ever know. Whatever the reason, Harriet remained close to members of the extended Imler family throughout her lifetime.

Harriet’s first child, James William Clark, (grandfather of Bud Renschler) was born October 5, 1863 in Allen County. He was followed by Genetta, born after the Civil War in 1867.

In September 1864 Harriet’s husband, William Clark, along with three of her brothers, Amos, James and William Imler enlisted in the 180th Ohio Infantry.

William Imler died on 28 Mar 1865 at New Bern, North Carolina. He left a widow and four small children. He is buried at Amanda Baptist Cemetery in Allen County, Ohio. Amos Imler died of disease on 12 June 1865 in McDougall General Hospital at New York Harbor, leaving a widow and one small son. He is buried in Cypress Hill National Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY.

Harriet’s husband William Clark, and her brother James Imler both survived to return home. However, William, who had contracted diphtheria and bronchitis while stationed at Camp Stoneman, Washington, D. C. and was treated at Douglas Hospital, later received an invalid pension for the damage to his health.

For many years I was unable to locate William and Harriet Clark on the 1870 federal census. It wasn’t until Familysearch.org indexed the 1870 census that I located them at Compton, Kane County, Illinois. William Clark, age 37, owned no real estate and only $200 worth of personal property. Mary age 18 and Abraham age 12 were listed as having attended school the previous year. James was age 6 and Genetta age 2. All were born in Ohio, so the family hadn’t been in Illinois long, and they didn’t remain there much longer. Why they went there and why they left no one knows. It is not on the route from Allen County, Ohio to southern Nebraska where the family moved next.

Clarice Clark Renschler Bugg told me stories about her grandparents which I wrote down. (She would not allow me to tape-record her reminiscence.) This is her story. “The Clarks homesteaded in Nemaha County, Nebraska. They brought two covered wagons filled with possessions, William drove one and Harriet the other. A cow was tied behind each wagon. One of the wagons was lost along the way while fording a river. It turned over and sank with all the goods and one horse. This was a terrible loss to the family.”

William built a sod house on the Nebraska homestead. “The roof was constructed from slabs—the first piece of wood cut from the side of a tree with the bark still attached. A heavy screen was placed over the slabs to hold straw, and over the straw, a layer of sod was placed. The window frames were wood and the floor was packed clay. One day William and Harriet were out milking and the two boys, Abe and James, were studying. Nettie, a small preschool child, about 3 years old, had often observed her father light his pipe by sticking a piece of straw into the stove and using it to light his pipe. She took a piece of straw, lit it in the stove, then touched the burning straw to a piece of straw hanging down from the low ceiling. The entire ceiling was soon ablaze and the children barely escaped with their lives. The house was completely gutted leaving the family with only the clothes on their backs. Needing shelter, they immediately cleaned the interior, plastered the walls, replaced the windows, and installed a wood floor to cover the clay one.”

The family lived in Nebraska about a year after the fire. The land in Nebraska was hilly and the soil was clay. There was no source of water nearby. Grandma Clark later said she would never again live on a farm without a creek running through it.

Dissatisfied with the Nebraska farm, the family moved to Jewell County, Kansas in October 1871, where William Clark filed for a 160-acre homestead in Section 2, Township 3 South, Range 6 West. This land is located in Grant Township, Jewell County, 2 miles north and 1 ½ miles east of Formosa, Kansas. There were few trees on the prairie, so they built another sod house.

On April 1, 1878 William filed his homestead proof at the Jewell County courthouse in Mankato. In it he stated that he had a wife and four children; he had settled on the land on the 2nd day of October 1871 and built a house thereon 16 by 24 feet, with 2 doors and 3 windows, dirt roof, dirt floor and had lived in the said house since October 1871. He had plowed and cultivated 40 acres of land and made the following improvements: “built a stable, hog pens, granary of pine, broke hedge rows, peach orchard, and dug a water well.” He received his patent one year later and filed it in Volume 15, page 28 of Jewell County deeds. It is unknown when the Clark family built a frame house to replace the soddie.

Pioneering in Kansas was just as difficult as pioneering in Nebraska. However, during the decade of the 1870s rainfall was sufficient to raise reasonable crops. On the 1875 Jewell County agricultural census William, age 41, has 160 acres, 127 of it prairie. In 1885 120 acres are still uncultivated indicating poor quality land. The Clark family was barely making a living. In 1881 William Clark applied for a pension because of disability suffered during the Civil War.

In 1885 both Harriet’s stepdaughter, Mary Elizabeth Clark, and her daughter, Genetta Viola “Nettie” Clark, married Harriet’s nephews who had followed the Clark family to Kansas. Mary Elizabeth Clark married George Christian Imler, son of Harriet’s older brother William Imler, who had died during the Civil War. George was 24 years old and Mary was 31 years old when they married at Mankato in April 1885.

Nettie Clark married, on June 27, 1885 at Mankato, her first cousin, Elijah B. Imler, son of Harriet’s brother, Amos who had also died during the Civil War. “Lij” as he was called, was a widower with a 4 year-old son. And, he was ten years older than 17-year-old Nettie. But she didn’t have many choices as she was four months pregnant.

The 1890s were hard years for farmers on the great plains, commodity prices were low, and railroad freight rates were unreasonable because farmers had no other way to get their grain to market. And, the country was in a depression. Then a severe drought struck in 1894 and farmers raised nothing. In the fall of 1895 William and Harriet, along with their son James and his family, Nettie and Elijah Imler, Mary and George Imler, and an unrelated Roy Jones family formed a small wagon train and moved to Van Buren County, Arkansas. The story is that a nephew of Harriet’s living there wrote describing how good life was there.

On the way down to Arkansas they were floating across a river and one of the wagons floated so far down river the bank was too steep to get out, so they threw some things out and kept floating until they found a low bank.

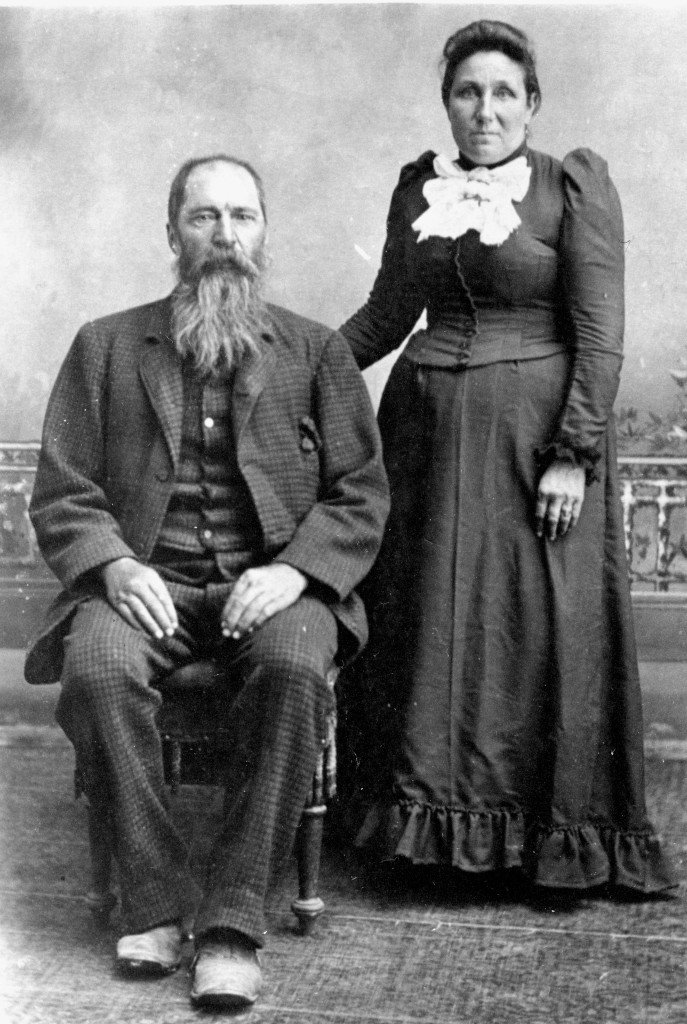

On April 19, 1897 William Clark, aged 64 years and two months, died at his home on Crowell Mountain in Van Buren County, Arkansas. He had gone out to the barn to lift up a colt that was down and he dropped dead from a heart attack. He is buried in the Crowell Cemetery in an unmarked grave. When Pat and I went there many years ago, the cemetery was in timber, hidden from the road which was merely a path up the mountain. Most of the graves were marked with fieldstones. Clarice told me that the day of his funeral it was raining heavily, the grave filled with water, and the casket, which floated, had to be weighted down with rocks.

On November 27, 1897 in Clinton, Arkansas, Harriet answered questions for a widow’s pension application. She stated “There was no public record kept of my husband’s death. He died very suddenly and I had no time to get a doctor to show the cause of his death.” She received $12 a month pension until her death.

When the Clark family returned to Jewell County, Kansas in 1898 Harriet moved back to the Clark farm which had been rented out. To settle William’s estate, his children, Abraham Clark and Mary Imler, by his first wife, and Harriet’s children James Clark (our ancestor) and Genetta Imler conveyed their interests in the farm to their mother for her lifetime. Upon her death, the four heirs were to divide the estate. Nettie, a widow and her children lived with Harriet. They are shown in her household on the 1900 federal census of Jewell County. On March 13, 1901 Harriet’s granddaughter, Lulu Imler, aged 15, died at Harriet’s home and was buried in the Balch Cemetery between the Clark farm and Formosa, Kansas. I do not know her cause of death and the brief item that appeared in the Formosa New Era newspaper did not give the cause of death.

Between 1909 and 1913 Harriet mortgaged her farm four times for a total of $4,540. What she did with the money I do not know, but suspect Nettie’s family got it. On August 18, 1913 Harriet signed a Last Will and Testament willing to “Janetta” Viola Imler all her interest in the farm. To Hugh Imler, “Janetta’s” son, she willed all her personal property. She gave her son, James Clark, $1. Harriet died five days later on August 23, 1913 and was buried in the Balch Cemetery.

But the story doesn’t end there. In November 1913 Genetta V. Imler petitioned for letters of administration for her mother’s estate. The farm was valued at $7,000, the house at $300, and personal items, including three cows and two calves, at $182.

Well, Mary E Imler, and Abraham Lincoln Clark, children of William Clark by his first wife, and James Clark, son of William and Harriet Clark weren’t going to give up their share of their father’s estate. On December 2, 1914, they sued “Jenette” Imler in Jewell County District Court and won. The farm was divided four ways. But of course, the mortgages had to be paid, the lawyers, and the court fees had to be paid. Each of the four received about $500. Grandson, Hugh Imler, received his grandmother’s personal property, including a new $98 top buggy that hadn’t been paid for and was part of the bills paid by the estate.

Grandma, Clarice Clark Renschler Bugg reminisced about her grandmother at various times and some of the stories she told me were: Grandma Clark had asthma and the doctor advised her to smoke a corn cob pipe twice a day, which she did. Harriet never returned to Ohio to visit her family, but several of them came out to Kansas to visit her. Harriet could speak German but didn’t want anyone to know that. One time a German immigrant was traveling through the country and stopped at the neighbors. The neighbors didn’t understand German, so they brought the immigrant over to Grandma Clark and she translated. Harriet was ill about two weeks before she died. Her skin turned yellow. The family thought her gall bladder ruptured a couple days before her death. Clarice was unable to attend her Grandmother’s funeral because she had just born her first child, a stillborn boy and she was in poor health.

And the last story. When I first visited Balch Cemetery in the 1970s I took Grandma Bugg along. I was surprised to find that several family member’s graves had markers, but Grandma Harriet Clark’s grave was unmarked. Clarice admitted nothing, but I was later told by other grandchildren, all now long dead, that Harriet’s grave had been marked by a stone ordered by Nettie. When she lost the court case, Nettie refused to pay for her mother’s grave marker, the other children refused to pay because they hadn’t ordered the stone, and eventually, the stone mason removed the marker from her grave. In 2002 a great-granddaughter placed a stone on Harriet’s grave and although William is not buried there, his name is engraved on the stone as well.