Edward John Kline’s World War II Experiences

As told to Catherine Trausch Renschler

By 1940 the government had initiated one year of compulsory military training. I enlisted on February 14, 1941. I went to Ft. Riley, Kansas and got my uniform, then was sent to Little Rock, Arkansas. There I joined Company G, 35th Infantry Division; the Hastings National Guard unit. Floyd Pressler and Dean Behrends of Trumbull were in the Hastings unit. I was in that Company until about two weeks before I went overseas.

The pay was $21 a month for the first four months, then $30 a month until I got out. $25 a month of my pay was sent home to the folks while I was overseas. We had to buy our tooth paste and shave cream and bar soap. Cigarettes cost four cents a pack—I didn’t smoke so I traded them for candy.

I was at Little Rock, Arkansas until December 1941. A week after Pearl Harbor we were sent to Camp San Luis Obispo in California. While I was stationed at San Francisco I got transferred to Company G, 164th Infantry. Twenty six of us were transferred to Company G, 164th Infantry Regiment of the North Dakota National Guards. We were based at Fleschackkers Play Field and Zoo, it was an amusement park. There was a tunnel, big enough to drive a car through that went under a road to the beach. We bunked in the tunnel. We did night beach patrol there, looking for lights. Some days we walked guard duty around the zoo.

I went overseas in March 1942; from San Francisco to Melbourne, Australia on the ship the USS President Coolidge. I was on the ship at Melbourne for six days. While there I got a one-day pass and went to a theatre.

At Melbourne we got off the USS President Coolidge after six days and got on a little cattle ship that sailed under the Javanese flag. It was pretty crude; we slept in hammocks. That ship took us to New Caledonia. We didn’t know where we were going; we were just on the ship. They didn’t tell us anything. When we got there we just went out into the woods and set up our tents. We were there for jungle warfare training. We carried M-1s, but we didn’t have any ammunition unless we were target practicing. We practiced with our bayonets. We carried our full pack–it had blankets, extra pair of shoes, shaving and bath stuff, socks and underwear. We were four platoons—three rifle platoons and one automatic weapons platoon. Each platoon had four squads of ten each, eight soldiers, one corporal, and one sergeant.

The people on New Caledonia spoke French and the natives spoke their language. In Noumea, the Capitol, the school kids were learning English

We were on New Caledonia until October 1942 when we were shipped to Guadalcanal on the USS McCaulay, a Marine transport. We were on the ship five or six days. They told us on the ship we were going to Guadalcanal. I had never heard of it before that. We landed on Kukum Beach on Guadalcanal on October 13, 1942.

On Guadalcanal the Marines and the Japanese had reached a stalemate. The Marines held about six square miles. We landed behind the Marine lines. The ship dropped anchor back 300 or 400 yards from shore on Kukum Beach. We crawled down those landing nets into landing barges. They put about a platoon in the barge for a trip to shore. The barge pulled up to shore and we walked off, I didn’t even get my feet wet. We could see the Japanese landing troops across the bay while we were landing. The first night we marched up to the place where we were going to take on the line. There was a line set up around Henderson Airfield to protect it. The Marines had been there since August when they took over a Japanese base, six square miles. The Japanese were already building this airfield. We had to stop that because if the Japanese got that airfield completed, then they could bomb Australia. Marines were manning the line and we replaced some of them. In the night, the first night I was there, the Japanese came in with their big battleships and our fleet left. The Japanese were stronger than we were and our fleet had to be careful.

The Japanese shelled us for two or three hours that night. Shrapnel was flying; occasionally you could hear somebody hollering. You can see those big shells coming, they were red hot. If they hit where the ground was soft they dug a big hole when they exploded.

Henderson Field was right on the ocean, the line was a half circle around the airfield, the ocean was on one side. All we had was a few fighter planes, maybe a half dozen, flown by the Army Air Corps. When the Japs came down with their bombers our fighter planes went up and shot at the Japs. Our planes were pretty slow getting up to the fighting altitude. The Japs had two observation planes on Guadalcanal—they didn’t do anything but harass us. They went up at night and threw flares out that lit up the whole place. They were small planes that they could hide in a cove someplace in the daytime. We called one of them Maytag Charlie. His plane sounded like a Maytag engine. He spoke good English, we could talk to him while he was up there aggravating us, and he talked back.

The food on Guadalcanal was mostly rice. The Marines had captured a warehouse full of rice. It had worms in it. We put it in big pots and skimmed the worms off and cooked it. We didn’t have any food because when they were unloading the ship, the men got off first, then the ammo. Then the bombers came in and the ship had to leave with our food still on it.

I was at the airfield on Guadalcanal sixteen days; then I was injured. The Marines came into our camp a little after dark one night; the Japanese had attacked the line in another place and they came to get our group to help them out. We marched over there—two or three miles– in the night. When we got there a battle was going on and we didn’t know what the hell to do. Nobody had told us anything. The Japs had made about a two-week march from where their base was. They had circled around and came in on the back side of our base.

Our Lieutenant had his own platoon. He said, “Everybody lay down over there and Ed and I will find out where they want to put us on the line.” He was from South Dakota. It was dark. We thought we were getting into dangerous territory so we laid down behind a tree. Then this bunch of Japanese who had just come through the barbed wire ran into us. I got up, but they jabbed the Lieutenant in the back before he could get up, and killed him right there. I was stabbed twice in my left arm. They didn’t shoot, probably because they didn’t want to give themselves away. I lost my weapon during the fight. I got away from them and ran into the jungle. The Japs stood around there and decided what they were going to do I guess. There were some Marines in a machine gun hole covered with logs close by there and they were out of ammunition. Their ammunition carriers were coming up and they both got shot and killed. I saw one of the Marines who was in the machine gun hole after he got out and he was shaking so bad he could hardly talk. The Japs had been jabbing at him with bayonets and he was kicking at them and finally he got away. I was out in the jungle all night. When it began to get light the Japs quit fighting and hid in the jungle. In the morning they were sniping from trees whenever they could get a shot off without giving themselves away.

When it got light I found the rest of my platoon. The Lieutenant and the medic had been killed that night. There was a lot of activity around there, they were out picking up the guys that were injured and killed. By then they were getting organized and a couple Marines would take a soldier with them. None of us had been in combat before. They split us up so they could get more good out of us.

The next afternoon they took me to the medical station they had on the island there. It was a hole in the ground with boilerplate over the top. There must have been eight or ten people down in there. It was deep enough you could walk around down in there. They had bunks in there. I was there until I left the island a day or two later. They put us on a plane and we flew to Hebrides Islands—Esperanto Santos—code name Cactus. There was a hospital there. It was in a Quonset hut, no ends in the building, just screens in the ends. I was there two or three days and never did see a doctor there. A hospital ship, the Solas, came in there and picked us up. I was six days getting back to New Zealand. We sailed into Auckland and then they took us on a train to Wellington. There was a large Navy hospital near Wellington, New Zealand. I was there until about December 20th.

I had surgery in Wellington to repair the severed nerve in my arm. The Doctor in New Zealand said “I’ve got good news and bad news. The good news is you are going to go home. The bad news is you’re going to be in the hospital from six to eight months.

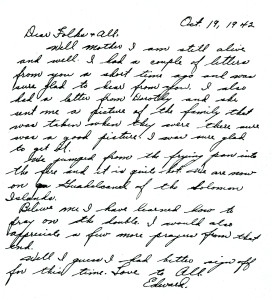

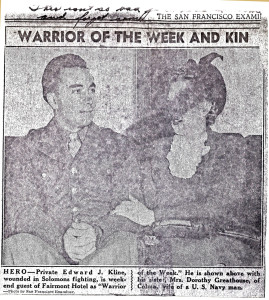

I got back to San Francisco on January 1, 1943. I went to Letterman Army Hospital at the Presidio. I called my sister Dorothy when I got there. I never got any mail after I left New Caledonia; I got some mail three months after I got home. They had it shrunk down into those little pages. While I was in Letterman Hospital a guy from the San Francisco Hotel Association came around and interviewed some of us, and I got picked to be the “Warrior of the Week.” They put Dorothy and me up in the Fairmont Hotel for the weekend. We could order anything to eat that we wanted. The San Francisco newspaper printed a photo and story about me.

I was in Letterman Hospital until February when they sent me to Hammond General Hospital in Modesto, California. After I got to Modesto they gave me therapy. They put a metal plate hooked up to electricity in the middle of my back. Attached to it by wires was a pencil-like probe, and they stuck it on my arm and a shot of electricity made my fingers move. I can’t straighten out my fingers on my left hand. The Doctor in New Zealand told me eventually my hand would go shut and I wouldn’t be able to use it at all, but I kept moving it.

I was in Letterman Hospital until February when they sent me to Hammond General Hospital in Modesto, California. After I got to Modesto they gave me therapy. They put a metal plate hooked up to electricity in the middle of my back. Attached to it by wires was a pencil-like probe, and they stuck it on my arm and a shot of electricity made my fingers move. I can’t straighten out my fingers on my left hand. The Doctor in New Zealand told me eventually my hand would go shut and I wouldn’t be able to use it at all, but I kept moving it.

While I was in Modesto I got a 30-day furlough and I rode the train to Fort Sill, Oklahoma and picked Grace up and we drove her car to Nebraska. She was teaching Home Economics in an Indian school. We were married in February 1943 at Harvard. We stayed at the folks place in their spare room. Gas was rationed so we left her car at the folks and took the train back to California. Grace stayed with Dorothy at Coloma, California. Dorothy was working waiting tables while her husband Archie Greathouse was in the Navy. Grace got a job in a factory packing department—they made blouses.

My records never did follow me; I never got paid from August 1942 until April 1943. I was discharged in May 1943 at the Presidio in San Francisco. I got on the bus in my uniform and Grace and I came home. The folks met us at the bus station in Grand Island. We lived with the folks for a couple months and I went back to farming, planted corn on Grandma Kline’s [Bertha Kline] place. I had farmed her place before I went into the service and I had rented the Snell place. Dad farmed the Snell place for me while I was gone. Clayton Snell was living in the house and we had to wait for him to get out so Grace and I could move in.

I was gone from February 1941 until May 1943. I was 30% disabled. I began getting $30 a month disability payments three or four months after I got home. While I was in the jungle I got a fungus under my toenails and I had to have all of them taken off later on. I received the Purple Heart, the Asiatic-Pacific Medal, the American Campaign Medal, a Good Conduct Medal, a Presidential Unit Citation, and a bar with a Battle Star.

Company G of the North Dakota National Guard suffered 85% casualties during the war. They went from Guadalcanal to Bougainville Island, and then to Japan as occupiers.

Thank you for this story Since I was so little during the war, I did not hear details like these. Thank you.

Catherine,

I printed this blog for Rita Kline Obermeier and gave it to her today (Aug 14, 2019) when I interviewed her for a story.

It is possible to get a clearer copy of the newspaper clipping from the San Francisco Examiner, as it is difficult to read?

I will also be calling on you soon for an idea/plan I have.

Paula Harmon Consbruck, Giltner (and Trumbull)